As a UK-based consenting lawyer with an energy focus, one of the most common questions from clients and colleagues is which type of consent is needed for a particular energy project. The differences in regime can be important in terms of appetite for cost exposure for a potentially more lengthy and costly process, which can vary greatly depending on which regime the project falls into.

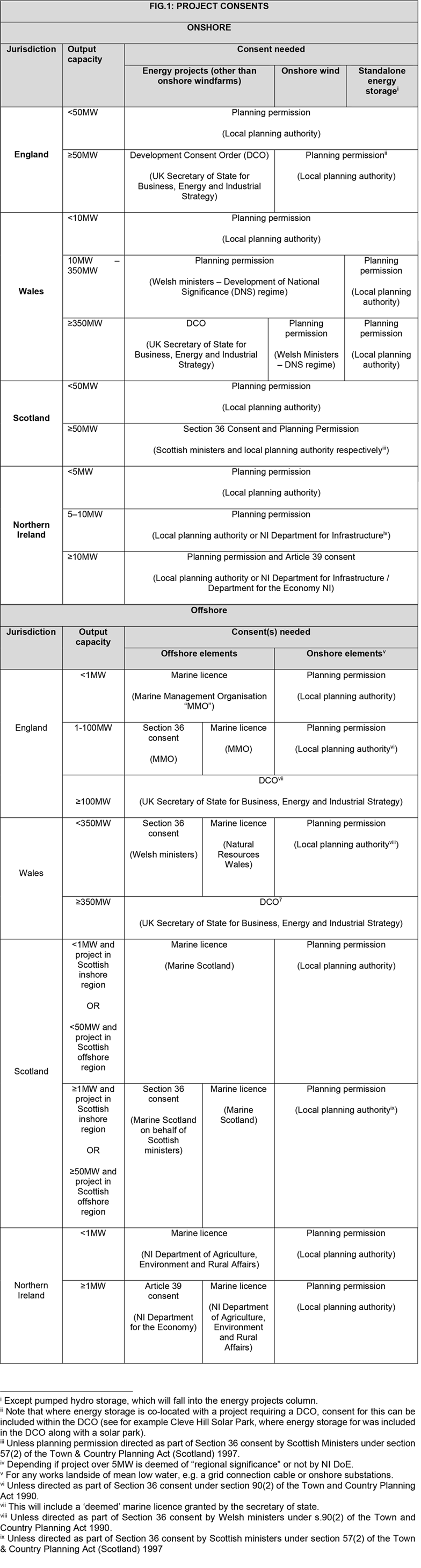

Which consent is needed depends firstly on which UK jurisdiction the project will be located within, secondly on whether it is onshore or offshore, and thirdly on its MW output capacity. This article seeks to provide an overview of what regime applies to what project and to set out some key features of each.

It is important to note that, once a project has consent, although regimes may change for the type of consent needed (for example, changes to which type of consent onshore windfarms need is, and has been, the subject of much recent debate in relation to England and Wales) the existing permit remains valid and there will be no requirement for a new consent. Therefore, often when undertaking due diligence on an existing project licences and consents may emerge that would not apply to a new project (an obvious example is a FEPA licence for a large English offshore windfarm, which was the predecessor of a marine licence).

The article considers only the key headline consents for construction and use—there are other permits that may be required in certain circumstances, such as European Protected Species licences, highways licences and so forth. In addition, other powers, such as for compulsory acquisition of land, may be needed to build out a project.

Overview

Below is a table that sets out a summary of which regime applies in which jurisdiction to which size of project. For clarity, when the table refers to ‘energy’ projects, this includes a range of generation technologies, including but not limited to:

- Wind (note the key differences between onshore and offshore below)

- Solar

- Tidal

- Nuclear

- Gas-fired power

In relation to offshore consents, the regime differentiates between elements that are offshore and onshore (likely to include powers to install and operate grid connection cables, substations and other works to connect to the grid), but in general offshore projects still require permits for onshore works. These consents may be granted by the same authority and as part of the same process as for the offshore elements of the scheme (see Fig.1).

Planning permission

Planning permission is a general requirement across all of the UK for the construction of works. Usually, planning permissions are granted by the relevant local planning authority for the area that the project is located in, and considered against local policy as well as certain national policies. Planning permission, once granted, allows the developer to construct the permitted development and use it in the manner authorised.

Planning permissions are almost always granted subject to conditions that regulate the construction or operation of the authorised project and are likely to include ‘pre-commencement’ conditions, which prevent the commencement of works until they are fulfilled. In addition, the developer may be required to enter into a planning obligation agreement under section 106 of the Town and Country Planning Act 1990, that may require contribution to infrastructure or services in the local area.

There are guidelines on timing, but this is largely in the gift of the particular authority and their own particular workload and pressures.

There are some deviations from the local decision-making for planning permission across the UK jurisdictions—the Welsh DNS process is covered below, as is the position for deemed permission as part of a section 36 consent. Along with these energy or infrastructure-specific processes, in each jurisdiction the relevant national or devolved government has authority to ‘call in’ certain applications to be determined where these are considered of importance nationally. In Northern Ireland, for example, an application that is considered a “major development” under the Planning Act (NI) 2011 may be determined by the NI Department for Infrastructure if that body considers it to have “regional significance”. For energy, a major development is a generating station with a capacity of over 5MW, so if the department considers such a project to have regional significance, it will determine the application.

Planning permission is an onshore permission, and does not cover activities beyond mean low water (this has a technical definition but is essentially a point on the coast where the average of low tidal waters is), however, this would be required for onshore elements of certain offshore schemes, typically grid connection cables.

An important point to note is that, in England and Wales, all energy storage (save for pumped hydro) and onshore wind projects require planning permission, regardless of their output capacity. In Scotland, a chief planning officer letter in August 2020 confirmed a different approach, that all storage projects would be treated as any other generation station with the same output categories.

In Northern Ireland, the energy storage position was set out in Chief Planner's Update 7 in December 2020, which affirmed that storage facilities would be considered as an electricity generation station, therefore falling within the same categories for treatment as ‘major development’. However, a recent High Court of Northern Ireland decision held that the publication of this guidance had not been based on a proper analysis of statutory provisions and had failed to give adequate weight to a prior appeal decision. The final position from the chief planner is therefore awaited, as it is likely that updated guidance will be issued on energy storage.

DCO

A development consent order (DCO) is a consent under the Planning Act 2008 (PA08) for “nationally significant” infrastructure in England and Wales. If an infrastructure project falls into a category set out in the PA08 (for energy projects in England, over 50MW output capacity onshore or 100MW offshore, or over 350MW for Welsh projects), or the applicant successfully applies for it to be included in this regime, instead of planning permission a DCO is required to construct and operate the project.

DCOs are granted by the relevant secretary of state (for energy projects this is the secretary of state for business, energy and industrial strategy). There are national policy statements for each type of development included in the PA08 regime, and these set out the need for the development and how the decision-making process should be undertaken, including relevant considerations for the secretary of state. Local planning authorities have a voice in the process, providing comments and representations but the secretary of state, considering a recommendation from an independent panel of inspectors, will make the ultimate decision.

The process has specific steps needing to be undertaken (including an emphasis on pre-application consultation) and in its examination phase, administered by the Planning Inspectorate, has prescriptive timings, with a six-month period for consideration of issues by the inspector or panel of inspectors, including written questions and hearings to consider specific topics. Consent then will be granted or refused within a six-month period following the close of examination (although there have been extensions to this in some recent applications).

The consent is in the form of a statutory instrument, giving the applicant a full suite of powers needed to build the project. It will be subject to conditions, known as requirements, which similar to planning conditions place limits on the power granted in areas such as methods of construction or operation of the project.

Other key features of a DCO include protective provisions, which manage the interface between the project and key statutory undertakers such as utility companies, for example, setting out a process for maintenance of cables where they overlap with existing pipes or cables. Similar to planning applications, the applicant may enter into a section 106 agreement to secure certain obligations.

Importantly, a DCO is a one-stop shop and so, for offshore projects, can include all powers needed to construct onshore works, and where a marine licence is needed (see below) this can also be granted by the secretary of state alongside the DCO. A DCO can also include compulsory acquisition powers, modification of legislation and other useful powers such as a defence to claims of statutory nuisance.

Planning permission – DNS

This consent process applies only in Wales, having been introduced by the Wales Act 2017 and the Planning (Wales) Act 2015. The process is run by the Planning Inspectorate Wales and consent decisions made by Welsh minsters in accordance with Welsh ministers’ national planning policy, and while it resembles the PA08 process, the outcome is a planning permission.

The DNS process is modelled on the PA08 process but is scaled back, with the same use of an examination by an inspector or inspectors appointed by the Planning Inspectorate Wales. The main differences include the shorter examination period (17 weeks versus six months for DCO applications), the lack of option to seek compulsory purchase powers, and the more limited scope of other consents that can be wrapped up in the process, applications for which are run in parallel to the main application with a separate consent, although determined by Welsh minsters too.

As noted above, two exceptions to this process are energy storage and onshore windfarms, which are excluded from the DNS regime and must be consented locally by local planning authorities.

Section 36 consent

Consent under section 36 of the Electricity Act 1989 spans three of the four UK jurisdictions (it does not apply in Northern Ireland), but applies slightly differently in each, and with different authorities deciding the application. While it is the main consent for large energy developments onshore and offshore in Scotland, in Wales it has slightly narrower use, for smaller offshore projects, and in England, since the advent of the DCO regime under the PA08 in 2010 it is most limited, being only for offshore developments between 1MW and 100MW, which are increasingly rare (although existing section 36 consents can be amended now under section 36C of the Electricity Act 1989).

There is a slight complication for Scottish offshore projects, as those which are closer to shore, in the “inshore” region (i.e. within 12 nautical miles) require a section 36 consent where the output capacity is in excess of 1MW, whereas those located further away, in the offshore region, being 12-200 nautical miles away from shore, will fall within this regime when in excess of 50MW output capacity.

For each jurisdiction a section 36 consent will not of itself provide planning permission, being a consent to generate electricity, so consent to construct must be granted either separately by the local planning authority or, more commonly, deemed by the authority granting the section 36 consent under relevant planning legislation (see notes Fig.1). This applies equally to onshore or offshore projects, save that in the case of offshore projects the onshore elements only would require this deemed planning permission.

In terms of process, much like other consents, there is an emphasis on public engagement and consultation, with the relevant authority holding public inquiries before making a decision on an application. The process from initial scheme design to approval can take around two years if a public inquiry is held to consider the application, which will be necessary where a local authority raise an objection or where the decision maker considers it necessary in light of objections to do so.

Article 39 consent

This consent under Article 39 of the Electricity (Northern Ireland) Order 1992 is only applicable to Northern Ireland. Much like section 36 consents, Article 39 consents are not in place of planning permission, which must be granted separately.

Interestingly, the Electricity Consents (Planning) (Northern Ireland) Order 2006 introduced the option for planning consent to be directed by the Department for the Economy in the same way as the secretary of state would for a section 36 consent, however, this has yet to be put into force by the NI government.

The same 2006 order also set out a framework for objections and holding of public inquiries for Article 39 consents. Again, this has yet to be implemented.

Guidance provided by the NI Department for the Economy does ask that applications be submitted at least four months in advance of the date construction is proposed to commence, so this should be a guideline on timing for these applications.

Reflective of the type of consent, and unlike planning permissions, the application for Article 39 consent relates in part to the applicant themselves, their background and capability to construct and operate the proposed energy project.

Marine licence

Any offshore project also requires a marine licence under the Marine and Coastal Access Act 2009 (MCAA), and for Scottish projects in the “inshore” region (0-12 nautical miles from shore), Marine (Scotland) Act 2010. This would be the only consent needed for the offshore elements of a project with an output capacity of less than 1MW. This consent is required in each of the four jurisdictions.

A marine licence is a licence to deposit objects on the sea bed, and therefore these can also be required for certain discrete activities after grant of the main project consent. An example would be activities where pre-construction monitoring may be required which involve seabed deposits.

In English waters, for projects over 100MW, and in Welsh waters over 350MW, this licence can be wrapped up with a DCO as a deemed consent, and granted by the secretary of state alongside the main order. Otherwise, the applicant must apply to either the Marine Management Organisation or Natural Resources Wales, respectively, for this licence.

In Scotland and Northern Ireland, a marine licence is also required, alongside either a section 36 consent or an Article 39 consent, respectively and granted by Marine Scotland or NI Department of Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs respectively.

In terms of process, the decision maker will consult with bodies such as the Maritime and Coastguard Authority, Trinity House and the local planning authority on the application and consider any environmental impact assessment undertaken before issuing a licence subject to conditions regulating the construction and operation of the development if it is satisfied with the application. There are no timeframes in the MCAA, as there is a need for flexibility given the breadth of application types. In Scotland, the application for a marine licence will be considered simultaneously with a section 36 consent application by Marine Scotland.

Conclusion

Before developing a project, expert advice should always be procured to ensure the correct consents are in place.

In particular, in an environment where technology is quickly making projects capable of higher outputs within the environmental impact parameters, careful consideration should be given to any estimate for output of a project made during the consenting stage, as in most regimes this will become a cap that may prevent substitution of more efficient technology when development commences. This has led to a trend in DCO consenting, where an applicant can put forward a proposed consent, to having only a minimum output (to ensure it is within the DCO regime) rather than an upper limit. Such an approach will make such projects more economically viable and therefore attractive to future investment and financing.

Peter Cole is a senior associate at Norton Rose Fulbright

Comments